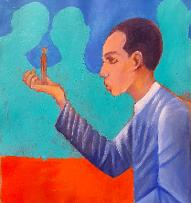

NARRATIVE PAINTINGS ILLUSTRATING A STORY OR REAL EVENT.

The Ottoman Graveyard

(A reconciliation) July-August 2021.

I grew up in a house built on a long-lost Ottoman army graveyard. This painting is about a history that was omitted by design as we were growing up.

This painting has its roots in my early childhood on the island of Crete. It has somehow wanted to find expression and over the years has surfaced in my stories and artwork. So when this image appeared on a canvas in 2021, I was not surprised. It is largely based on a photograph for a postcard by E. A Cavaliero from the late 1800s. The caption in French reads Costume Turc Crétois. In other words, the photographer captured the dress code of Cretans in the late 1800s. But these were not just any islanders. They were Cretan 'Turks', Τουρκοκρητικοί or Τουρκοκρήτες, Tourkokritikí or Tourkokrítes,

Turkish: Giritli, Girit Türkleri, or Giritli Türkler, Arabic: أتراك كريت), in other words, Greek speaking muslims. The vast majority of Muslim Cretans were indigenous to the island, converted to Islam, but retained the Cretan dialect and traditions. It is assumed that many belonged to Catholic families who had benefitted under Venetian rule, but I cannot substantiate this assertion with accurate figures. When I first saw Cavaliero's photograph some years ago, I was surprised. I knew from Ottoman population censuses that Crete had a large number of Muslims, who eventually were forced to leave in an exchange of populations in 1923. I did not know all the details, but as a child of refugees coming the other way, so to speak, (From Turkey or a rather 'pre-Turkey' Asia Minor, to Crete) I knew the pain of displacement. Of course, all this was not discussed when I was a child, but it was there. I sensed it often.

In our garden in the suburb of Mastaba, (spelled Μασταμπάς or Mastampas) I found a long bone whilst 'digging for treasure' in our long-vanished house garden. I showed it to my mother who calmly said that it probably belonged to a domestic or a farm animal. I did not actually believe my mother, but I think I wanted to. It is clear that the experience remained with me and I have tried to depict this childhood experience in a number of ways over the years, either directly or in a symbolic way and the images below are just two of those attempts. I employed at that time a children's book illustration style.

The above imagesare part of an illustrated book and are not part of the exhibition.

Many years later, whilst researching for a book on the little-known Arab Emirate of Crete (827-961 approx.) I was amazed to see that one of the Arab coins minted on Crete itself was found in Mastampas, the place where I grew up. Mastampas/Mastabas was a peculiar name for a Greek suburb, but we all accepted it. The history of Crete meant that many Italian, and Turkish place names remained, and we never questioned their providence. It is so obvious to me now, that Mastampas or Mastabas comes from the Arabic word for a grave. I think that is how it passed down into some sort of common parlance during the Ottoman era and I surmise from all that I have read that the Ottomans adopted the term as a geographical designation, based on what they knew about its prior use.